In one of my previous posts, I displayed the rather humiliating video clip of a Presidential candidate standing before a hostile crowd trying to explain why he supported a recent Supreme Court decision. The decision in question was that of the fantastically misguided Citizens United ruling which, in effect, inferred that corporations have rights comparable to citizens. "Corporations are people too, my friends," he pleaded, while the hecklers heckled and others just laughed in his face. Needless to say, it was an exercise in futility. Common sense prevailed, despite Romney's attempts at persuasion.

In one of my previous posts, I displayed the rather humiliating video clip of a Presidential candidate standing before a hostile crowd trying to explain why he supported a recent Supreme Court decision. The decision in question was that of the fantastically misguided Citizens United ruling which, in effect, inferred that corporations have rights comparable to citizens. "Corporations are people too, my friends," he pleaded, while the hecklers heckled and others just laughed in his face. Needless to say, it was an exercise in futility. Common sense prevailed, despite Romney's attempts at persuasion. Sometimes it’s helpful to take a step back in order to figure out how a certain strange contemporary situation developed. How, for example, could the Supreme Court of the United States- a collection of presumed sane and wise judges- have ever decided, against all logic and common sense, that corporations are deserving of equal rights granted to actual breathing human beings? How could these presumed enlightened scholars have ever put their hoary heads together and come up with this?

It’s fairly easy to simply throw up one’s hands and claim that the Koch brothers (or some other multi-national corporation) have infiltrated the courts, just as they have infiltrated the legislative branches and just as they are now attempting to purchase the executive branch. There’s plenty of evidence for this claim, of course.

But I am more interested in seeing how this strange state of affairs could have ever gotten to this peculiar point. How did a corporation- essentially a legal construct- become a person, equal under the constitution, to any American citizen?

Conception

Writer Stephen D. Foster explains:

The East India Company was the largest corporation of its day and its dominance of trade angered the colonists so much, that they dumped the tea products it had on a ship into Boston Harbor which today is universally known as the Boston Tea Party. At the time, in Britain, large corporations funded elections generously and its stock was owned by nearly everyone in parliament. The founding fathers did not think much of these corporations that had great wealth and great influence in government. And that is precisely why they put restrictions upon them after the government was organized under the Constitution.

However, mostly for the sake of discussion, I would prefer to think of the East Indian Company as a tool of the British Empire, rather than as the corporation, that we define them today.

It’s true, of course, that corporations have often served similar purposes in American foreign policy. In the British example, government- or rather, the Crown- remained in control of the corporation, at least on the surface. In the later American model, that was much less true and corporations tended to look out completely for their own self-interest, irrespective of government policy. Thom Hartman writes in his book, “Unequal Protection”,

Trade-dominance by the East India Company aroused the greatest passions of America’s Founders – every schoolboy knows how they dumped the Company’s tea into Boston harbour. At the time in Britain virtually all members of parliament were stockholders, a tenth had made their fortunes through the Company, and the Company funded parliamentary elections generously.

As a side note: It is perhaps ironic that the Occupy Wall street protesters objections to corporate over-reach are much more reminiscent of the Boston Tea Party than the modern-day Koch-funded sponsored Tea Party movement.

In any case, let’s move past that and hover our time machine over America of the mid to late 1800s..

Pangs of Corporate Birth

The rise of the corporation from its early forms into what it has now become is important for our understanding of our own time. First of all, it is important to note that corporations were once private, or semi-private entities, specific and carefully regulated enterprises. As one source tells us:

After the nation’s founding, corporations were granted charters by the state as they are today. Unlike today, however, corporations were only permitted to exist 20 or 30 years and could only deal in one commodity, could not hold stock in other companies, and their property holdings were limited to what they needed to accomplish their business goals. And perhaps the most important facet of all this is that most states in the early days of the nation had laws on the books that made any political contribution by corporations a criminal offense.

In the book, Socializing Capital: The Rise of the Large Industrial Corporation in America, Author William G. Roy observes:

The corporation.. has not always been a private institution. Corporations were originally chartered by governments to accomplish public tasks, to build roads, construct canals, explore and settle new lands, conduct banking and other tasks governments felt could not or should not be conducted privately. Contrary to the notion that corporations autonomously developed because they competed more efficiently or effectively in the market, governments created the corporation form to do things that rational businessmen would not do because they were too risky, too expensive, too unprofitable or too public, that is, to perform tasks that would not have gotten done if left to the efficient operations of markets. Corporations were developed to undertake jobs that were not rational or not appropriate from the perspective of the individual businessman.

In the early industrial age of America, the task of building an effective infrastructure was left up to chartered corporations. Virginia Rasmussen from Program on Corporations, Law and Democracy (POCLAD) points out:

The charter of the corporation was given by state legislatures and state legislators were the only figures in government actually elected by the people. That's where they placed the chartering of corporations and those charters were very specific in their content. The purpose of the corporation was made clear: a corporation could not suddenly start doing something outside of that purpose. They were liable for harms done; their records had to be open to the public at any time; they were subject to trial by jury; they could not own stock in other corporations; they were limited to a certain size and they could be brought before a legislature or state courts and have their charter revoked when they violated this publicly granted agreement.

After the government contracted work had been achieved, the project would then be sold off to the private sector at a shared profit to both the corporation and the government. Roy adds this:

..From a perspective of the early nineteenth century, private ownership and control of corporations were not viewed as inevitable. The nation's largest bank was federal. Most infrastructure was mixed ownership... Only the late entrant, the railroad, which waited until the 1830s to begin, became privately owned.

The state governments would issue investment bonds to pay for the projects, as well as supplying land and labor. But many investors were soon to realize that the bonds could easily be rendered valueless by unregulated speculation. The stock market crashes of 1837 and 1857 caused one state after another to default on loans for projects.

Illinois, for example, picked the inopportune year of 1837 to create a major internal improvement project authorizing the sale of $8 million in bonds to finance seven railroads and navigable river. The crash and the depression that followed caused its complete failure and the state default on its loan.

The resulting economic crisis effectively put an end to European investment for years afterward. The government was blamed for the disaster and the backlash that resulted caused a major re-evaluation of government supervised corporations. As Meyer Weinberg in A Short History of American Capitalism explains:

By 1840, the model of the public tightly- restricted corporation was quickly becoming obsolete. And by 1850, the past form was gone altogether, replaced by an aggressive new form of corporation in which government played the role of tax-collector and legislative facilitator.Until the second quarter of the 19th century, state charters of incorporation were passed singly by the legislature. After a time, a movement began to enact a general incorporation statute which required only an administrative application and payment of a modest fee.

As industrialization began reshaping America, great fortunes began accumulating in the hands of canal owners and financiers and later railroad and steel magnates. And as great fortunes accumulated, a new wealthy class began influencing policy-making, changing the rules governing the corporations they owned. Charters grew longer and less restrictive. The doctrine of limited liability – allowing corporate owners and managers to avoid responsibility for harm and losses caused by the corporation– began to appear in state corporate laws. Charter revocation became less frequent, and government functions shifted from keeping a close watch on corporations to encouraging their growth. For example,between 1861 and 1871, railroads received nearly $100 million in financial aid, and 200 million acres of land.

The scope of the power corporations might have expanded but the oversight by regulators could not keep up and in fact, decreased.

Eventually the bottom line became the most important factor. And that meant immediate profits to give investors a bankable return and this remained the dominant driving force behind corporations.As corporations grew in size and influence, however, their accounting structure remained the same. For a small corporation driven by investors, it made sense to measure corporate performance by measuring financial profits and losses. But for a corporation with thousands of employees and millions of customers, a corporation that was receiving public subsidies and encroaching on communities, a more extensive reporting system that measured the impact of the corporation on people’s lives might have made sense.

|

| Laying of the Transcontinental Railway |

Of all of the chartered corporate projects of the 19th century, none had a more powerful long term impact than the construction and utilization of the railroad system. Its success guaranteed the further development of the corporation.

In the span of a little more than a generation, this new form of corporation, unshackled by government authority, with the seemingly limitless reservoir of natural resources- untapped continent at its disposal, the corporation had taken up that challenge and transformed a nation.

With the advent of the railroad, the means of moving resources to the centers of manufacturing or shipping quickly transformed the nation of unexplored frontiers into an up-and-coming world power, a rival to the European empires.

With the industrial revolution transforming the nations of the world, machine-driven manufacturing required a constant flow of raw materials. And in that, the railroad was the ideal vehicle. Had the United States relied solely on its system of roads and canals, the history of the nation might well have been quite different.

As the lands beyond the Mississippi opened up, revealing new sources of wealth in the frontier, railroads became a dominant corporate power. As Roy notes:

No economic sector was as important to the rise of the large American business corporations as the railroads. Indeed, until the end of the nineteenth century, railroad companies and large corporations were synonymous. For example nearly all corporate securities traded on the stock market were railroad securities. Corporate law was primarily railroad law.

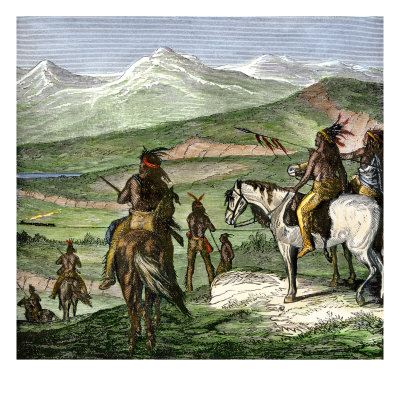

However, the unleashed corporation found its first victims, the North American continent’s indigenous people. The West was ripe for the taking and who ever stood in its way, would suffer the consequences. As one historical study states:

Westward construction proceeded very quickly over the open terrain of the Great Plains. Soon, however, they entered Indian-held lands. The Native Americans saw the railroad as a violation of their treaties with the United States. War parties began to raid the labor camps along the line. Union Pacific responded by increasing security and by hiring marksmen to kill Bison (commonly known as American buffalo) which were both a physical threat to trains and the primary food source for the Plains Indians....And the misgivings of the Native Americans were proven absolutely accurate.

The rail line gave the hunters convenient access to markets, and soon there was a widening gap in the bison herd as the hunt progressed outward from the rails. Estimates put the population of bison at the beginning of the 19th century at 30 to 100 million over all of North America. By the mid 1880's the population was down to a few hundred.

As if the destruction of their land and their culture wasn't bad enough, later, still worse was to follow. When the surviving generations of Native American, essentially refugees on their own land were officially promised their own state, that is, an independent state within the nation. Unfortunately the land would found to harbor petroleum and the plan would be scrapped for a the sake of the oil corporations.

Dr. Durant - Prototype of CEOs to Come

Even as late as May 10, 1869, the First Transcontinental Railroad, which connected both continental coasts, could not have been done without government assistance. The corporation responsible for the construction, The Union Pacific Railroad, was incorporated on July 1, 1862 under an act of congress and approved by President Abraham Lincoln- initially as a part of the war effort.The construction and operation of the line was authorized by the Pacific Railroad Acts of 1862 and 1864 during the American Civil War. Congress supported it with 30-year U.S. government bonds and extensive land grants of government-owned land. Completion of the railroad was the culmination of a decades-long movement to build such a line. It was one of the crowning achievements in the crossing of plains and high mountains westward by the Union Pacific and eastward by the Central Pacific.In addition to labor and materials, the railroads obviously needed large amounts of capital. Since the federal and state governments saw the railroads as a boon to national and local economic prospects, they were willing to underwrite much of the cost by distributing to the railroads the one commodity which they held in abundance: land. Across the vast open spaces in the West were millions of acres of arable land. That resource, however, could not be converted into profitable farming land without some means for the farmers to get their produce to market.

|

| Thomas Clark Durant |

Like every bubble, excessive and sudden infusions of money from speculators caused abnormal growth in the industry. The government regulators were swamped (or bribed) by this agitation in the market. One of those ready, willing and eager to profit from this lack of oversight was Thomas Clark Durant.

In order to dodge the regulations, Durant found improper means to avoid the government prohibition against concentrated ownership and meanwhile, manipulated the stock market price of his shares in the company by issuing false claims. Additionally, by overcharging on each mile of track and laying unnecessary extra track, he cheated the government- which was too preoccupied with the Civil War to address oversight of rail line construction. To top all of this, Durant managed to make a fortune by smuggling contraband cotton from the Confederate States

|

| Credit Mobilier Scandal 1872 |

To complete this sordid tale of an early corrupt corporate head, Durant lost most of his wealth in the panic of 1873 and spent his remaining years fighting lawsuits. Chalk it up to ignoble end to an unethical career.

The true legacy of Durant was the new corporate means of conducting business, divorced from its parent and benefactor, the United States government, the determination to use whatever means it took, legal or otherwise, to muster and retain power; the power it needed to remain in control of its destiny.

------------------------

No comments:

Post a Comment